Excerpted from Charles Thomas Cruttwell, A Literary History of Early Christianity, volume 1 (London: Charles Griffin and Company, 1893).

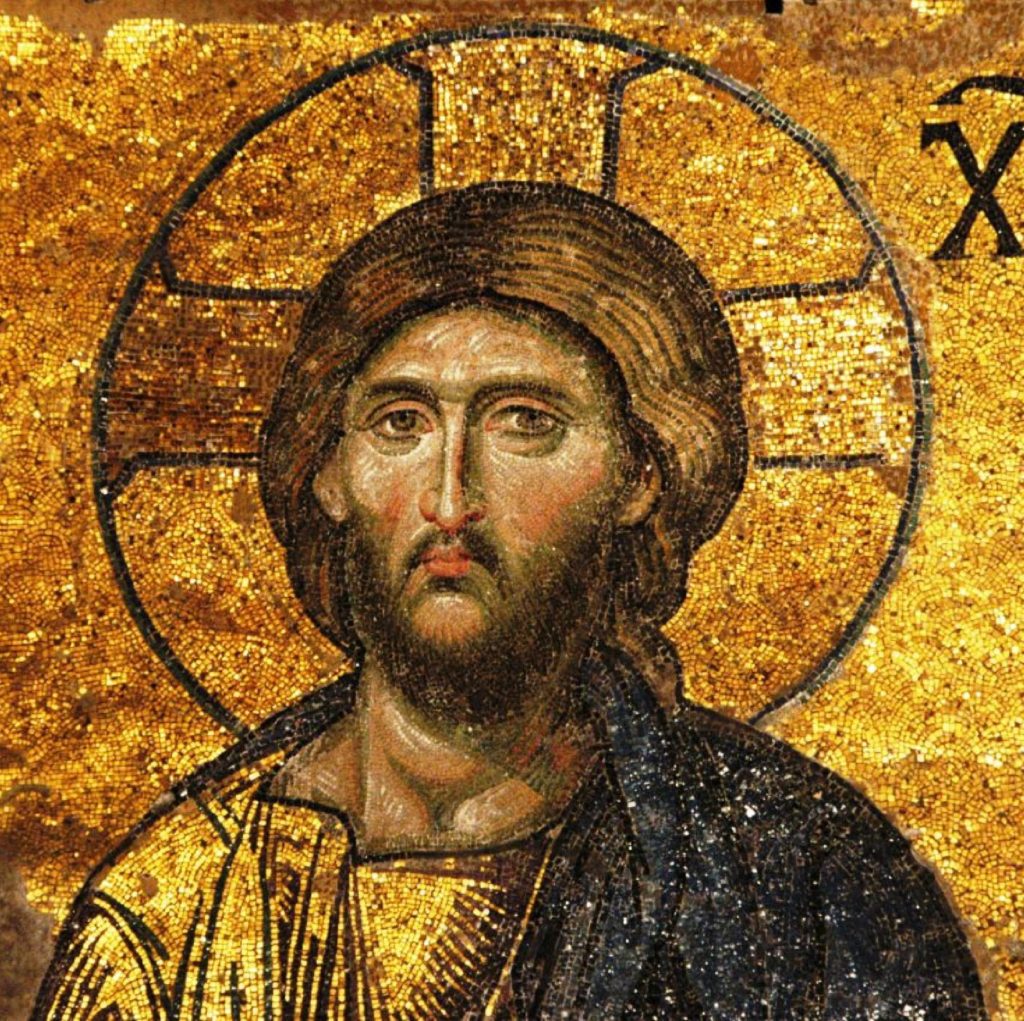

Historians have remarked that under stress of persecution or extreme spiritual trial the religious consciousness tends to express itself in that symbolic and imaginative style which we call Apocalyptic. This was specially the case with the Jews during the great war of liberation under the Maccabees. And after the destruction of Jerusalem by Titus, and again by Hadrian, the same tendency reappeared, and was even more prolific of results. Nor was it wholly unknown in the Christian Church. An example of it stands imbedded in the New Testament, the most mysterious and disputed of the writings of the canon. The Revelation of S. John has ever been the favorite study of a certain class of theologians, to whom the enigmatical is more attractive than the evident, and historic anticipation more congenial than inductive research.

To us this wondrous book stands apart like a cloud-capped peak, in isolated grandeur. But in early times its solitude was shared by a companion somewhat less inscrutable, if somewhat less authoritative, bearing on its title-page the honored name of Peter.

Until last year this work was known only by a few paltry fragments and some scattered allusions. But quite recently the French Archaeological Mission at Cairo have published three early documents of first-rate interest, though unfortunately incomplete, viz ., parts of the Book of Enoch, of the Gospel of S. Peter, and of what is universally admitted to be his Apocalypse. Nearly half of the latter is preserved, sufficient, that is, to form a fair estimate of its value, and to enable us to indicate its influence on succeeding literature.

We begin by mentioning the chief early notices of this supposed Petrine work. The first occurs in the Muratorian fragment on the canon ( A.D. 170–200), where, according to the received reading, it is placed among the Canonical Scriptures along with the Apocalypse of S. John, though with the qualifying remark that some members of the Church objected to its being publicly read.

The next writer who mentions it is Clement, who, according to Eusebius, commented on it in his Hypotyposes, and this statement is confirmed by three quotations in an existing

fragment of that work , one of which speaks of it as Scripture.

S. Methodius of Olympus, in Lycia (A.D. 300 ), also quotes one of these and says that it comes from “ divinely inspired writings.”

Eusebius, a little later, includes it in a list of the Petrie writings with these cautious words, “ The book (so-called) of his Acts, and the (so-called) Gospel according to Peter,

and what is known as his Preaching, and what is called his Apocalypse, these we know not at all as having been handed down among Catholic Scriptures, for no ancient Church writer nor contemporary of our own has made use of testimonies taken from them.” In the face of the citations from Clement and Methodius this last statement cannot be called correct, nor can the former be reconciled with the present text of the Muratorian fragment. In another passage Euse bius classes it with those spurious books which, though pseudonymous, are not of heretical tendencies and were considered by more indulgent critics as only disputed, i.e., of doubtful authenticity.

About a century later Macarius Magnes, refuting the objections of a heathen adversary, refers to bis use of this book as a standard Christian work. Macarius evidently disbelieves its genuineness, but accepts its teaching as orthodox.

Sozomen (about A.D. 450) testifies to its public use once a year on Good Friday by the churches of Palestine in his day, though he admits that the ancients generally considered it spurious.

Nicephorus (about A.D. 850) , in drawing up a classified list of inspired writings for practical use, places this book among them, though in an inferior position, and assigns it a length of three hundred lines, or a little shorter than the Epistle to the Galatians.

On looking back upon this record, we find that the Apocalypse of Peter held an honorable but precarious position among deutero-canonical writings, being in all probability accepted in Rome in the second century, and certainly in Egypt, Lycia, and Palestine, while it continued to be transcribed as late as the ninth century in Jerusalem , and no doubt also in Egypt.

It is further probable that Hippolytus of Portus (A.D. 220) made use of it: and clear traces of its employment are found in several later documents, such as the “First Book of Clement, or Testament of our Lord Jesus Christ ” (a work proceeding from the same source as the Clementine Recognitions), the Second Book of the Sibylline Oracles, and the History of Barlaam and Josaphat.

The language of the newly-discovered fragment shows moreover such evident connection with that of the second Epistle of S. Peter that, though it is without a title, there can be no question that it belongs to the Petrine cycle, and may be confidently accepted as part of the long-lost Apocalypse. Its date cannot be certainly determined : but the opinion of scholars seems to be in favor of a very early origin, going back to quite the beginning of the second, or possibly even to the last years of the first century. It will thus be among the most ancient relics of Christian literature, and this antiquity is rendered more probable by its qualified canonical recognition in spite of the peculiar nature of its contents. The existing portion is divisible into three parts, a prophetic discourse of Christ with His Apostles, a description of Paradise, and an Inferno or account of the punishment of the wicked. There is little to indicate any particular tendency in the work . It is built on the strong instincts of the religious imagination, and has evi dently influenced the popular belief of Christianity in no slight degree. Its interest is so great, that we think our readers will prefer to have some specimens put before them rather than any general criticism of its contents:

promethazine 25mg drug – purchase lincomycin pills buy lincocin 500 mg pill

Your comment is awaiting moderation.